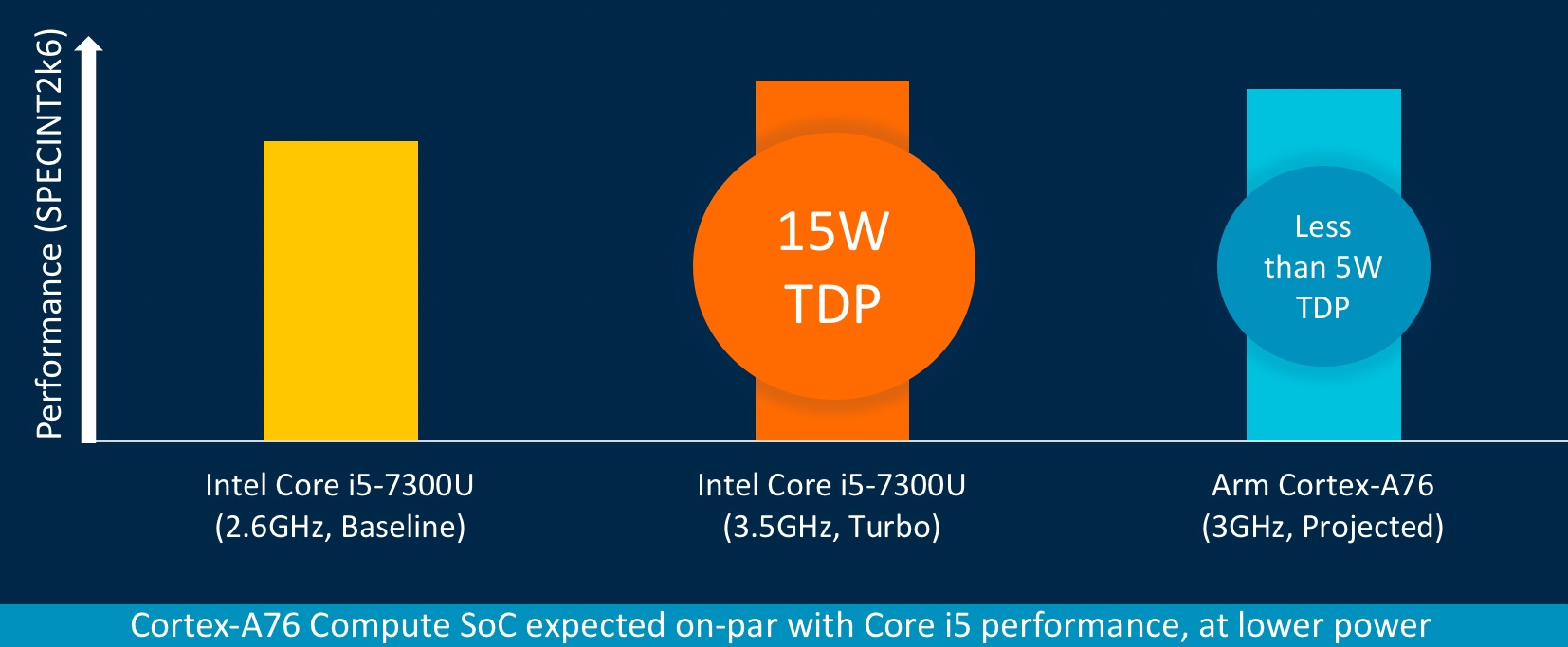

While most of today’s Chromebook models are powered by Intel processors, there could be a rise in device choices using Arm chips very soon. That’s what I get out of Arm’s public roadmap, which suggests its Cortex-A76 architecture should perform like an Intel Core i5 processor while using much less power.

To be fair, the graphic showing this is a little disingenuous if you don’t carefully inspect the information. For example, the Core i5 processor in the above comparison is a seventh-generation chip; that was introduced by Intel back in the first quarter of 2017, i.e.: roughly 18 months ago. Intel now has eight-gen chips available.

Additionally, the power usage of the Intel chip is shown in Turbo mode. The Core i5-7300U can be ratcheted down to 800MHz during times of lighter processing scenarios, in which case the TDP of the chip is 7.5W.

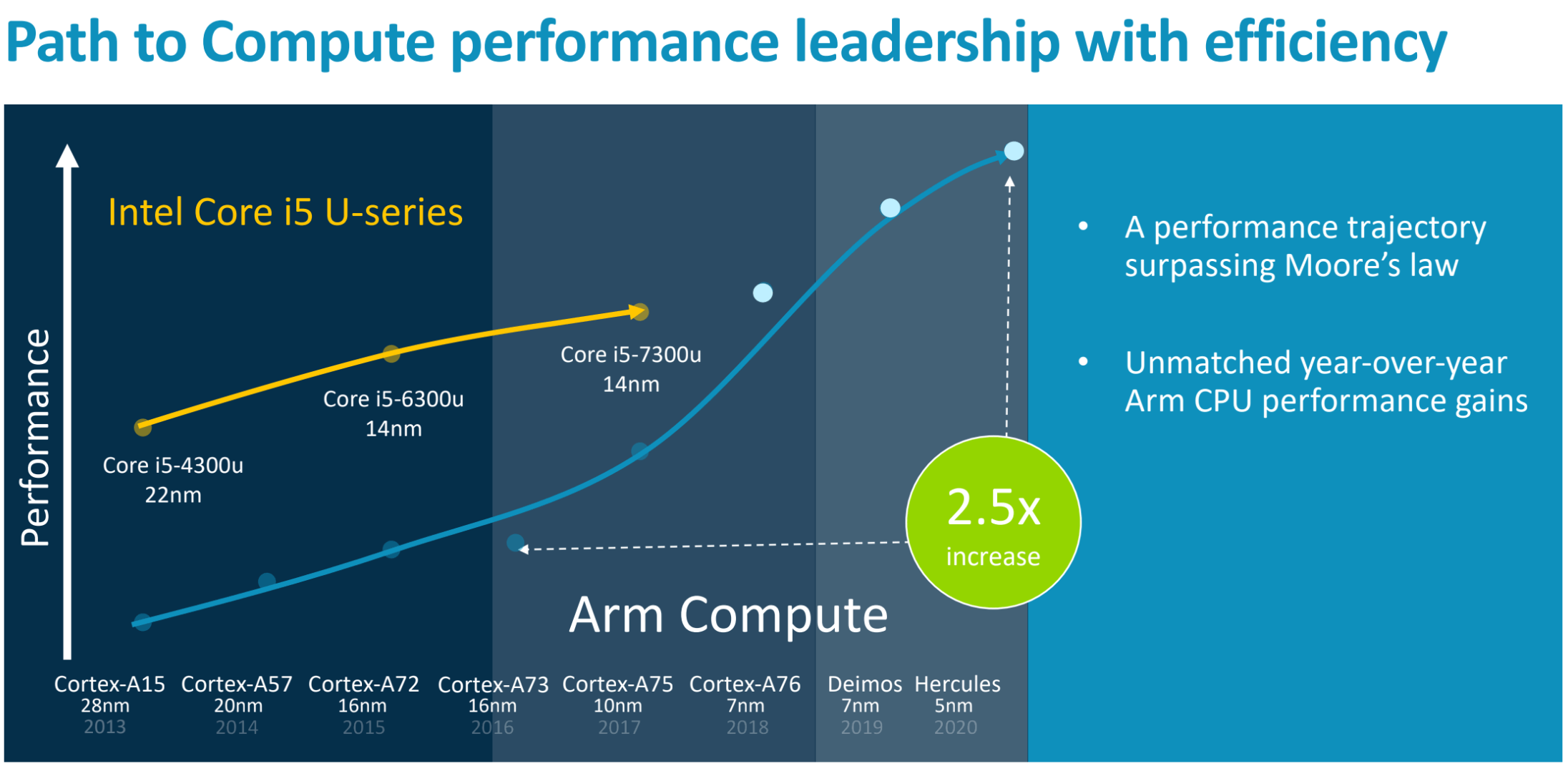

Even so, this is a positive step for Arm processors and illustrates the difference in how we got here.

Intel spent years adding more cores and faster clock speeds at the price of power requirements, which negatively affect run time on a battery charge. Arm started from the bottom up by slowly increasing performance while maintaining low-power requirements. Now we’re effectively starting to meet in the middle.

Indeed, Arm is predicting its chips will surpass Intel’s in terms of performance while still having devices with longer battery life, all things being equal.

So what does this all mean when it comes to Chromebooks?

I’d anticipate that more Chrome OS hardware partners consider using Arm-based processors in their Chromebooks over the next 12 to 24 months. That may not impact device pricing: In some cases, Arm chips have steadily increased costs for device makers while Intel has generally held cost increases down.

But it would still be a win for Chromebook buyers who wouldn’t be sacrificing much — if any — performance while getting longer battery life on an Arm-powered Chromebook. We’ll get a better sense of that theory when testing the Cheza Chromebook — powered by Qualcomm’s Snapdragon 845 Arm-architected chip — hits markets, possibly by the end of this year.

3 Comments

The last three ARM points are projections, not even hardly what’s available right now, and the last point is beyond the year 2020. Marketing voodoo?

Well, this is an interesting speculation isn’t it? I guess we’ve got a 24 month credibility gap to be crossed and after that we might know where market acceptance gets to by about the 48 month mark. By then all the current CBs will be near the end of Google’s support life so there may well have been many other factors influencing the results at that stage.

Well, not prejudging this certainly involves not prematurely crediting ARM’s claims before they deliver. But they could nonetheless deliver and I hope they do. Intelligent debate about where all of this may be heading has often focused on the evident energy efficiency advantage that ARM mobile SoCs have relative to Intel parts as well of the difficulty of building a compelling general argument for the preferability of energy efficient parts for business grade computers, when for undeniable physical reasons it is both easier and cheaper to produce high performance parts that forgo a heavy emphasis on energy efficiency.

Now, it is true that energy efficient parts (all things being equal) will cost more to make. And, so it is said by critics of ARM and its licensees that their business approach will always lead them into slim margins that puts a brake on architectural innovation while Intel rakes in healthy profits that lets them maintain or even extend their design lead.

This reasoning too quickly affirms Intel’s business approach, in my view. ARM is doing very well as an architecture without resorting to Intel’s approach to profit taking. ARM licensees turn out relatively few processors produced in very large volumes and although they are limited in scope no company making mobile devices is rushing to obtain Intel’s alternative. That says a lot. Furthermore, if you can’t sell many processors, no matter how much fatter the margin may be on those processors you’re still not going to make a profit on them. It wouldn’t surprise me if Intel continues to lose money on its low power parts, just as it did when it gave them away for next to nothing in order to buy a presence in the mobile device market. Those processors are crap (the low power Y series processors are an exception) and if manufacturers can’t get them for nothing they don’t want them.

Now, if we assume for the sake of argument that ARM can build high performance CPUs that are comparable to Intel’s then Intel will certainly be under pressure to dump its existing strategy of maintaining fat margins on its high performance processors. Any notional advantage Intel has over ARM – due to the higher cost of production of an energy efficient processor – dissipates if Intel fails to discount its processors relative to ARM parts. A high performance part may be good but a high performance part that is also energy efficient is better when it costs you no more. Unless Intel is willing to drop prices ARM will always be in a position to challenge Intel even in the supposedly safe territory of business computers. And if Intel does find it necessary to adjust its business strategy that is also a win for ARM in different way – Intel ceases to rake in such big profits and becomes more vulnerable to a well executed ARM technical and commercial strategy.

Finally, the evidence grows daily that ARM is right: the achievement of energy efficiency is an essential feature of sound design and necessary for long term commercial viability for all processors, not just mobile SoCs. In addition to initial outlays the correct standard of costs for a computing system include the operational costs over that life of the computer. When you look at things in that way energy efficient devices almost always win.