Sparkplug, a new mid-tier V8 compiler, will speed up JavaScript sites on Chromebooks, using less CPU power

This morning, I came across an interesting little project that the Chromium dev team has been working on over the month of February.

It’s called Sparkplug, and while I don’t understand all of the low-level workings, I do understand the goal. Sparkplug is an “interpreter accelerator” for Chrome’s V8 engine that will compile bytecode to machine code. This means it will improve website performance on Chromebooks while using less power.

The Sparkplug design doc overview section explains what’s being worked on and why:

There is a trade-off space for compilers which balances compilation time and compiled code quality. The Ignition interpreter and the TurboFan optimising compiler are at two ends of this spectrum. However, there is a big performance cliff between the two; staying too long in the interpreter means we don’t take advantage of optimisation, but calling TurboFan too early might mean we “waste” time optimising functions that aren’t actually hot — or worse, it means we deopt. We can reduce this gap with a simple, fast, non-optimising compiler, that can quickly and cheaply tier-up from the interpreter by linearly walking the bytecode and spitting out machine code. We call this compiler Sparkplug.

Here’s a look at some of the early test results of Sparkplug as compared to some of the current tools in V8 that render JavaScript, which is an interpreted (read: not compiled) language.

Note that Chrome’s V8 engine currently uses TurboProp, TurboFan, and Ignition in the V8 engine to interpret, compile and render JavaScript in Chrome. Lower bars, representing faster performance, are better.

The speed difference between SparkPlug and current V8 tools may not look that drastic, but keep in mind, this is for a single web page.

If the browser can speed up JavaScript by a few seconds on every page view, those seconds can add up over a long session. It may even be noticeable in overall browser snappiness in a short online session.

And it doesn’t require new hardware: It would help on every Chromebook currently out in the market that still gets software updates.

But there’s more.

This information from the design document outlines a another key benefit that come along for the ride:

Sparkplug by itself (without even TurboFan) has the lowest total CPU usage, which is valuable on pay-per-cycle servers and battery-powered devices.

That means whatever Chromebook you have, whether its powered by a lowly Celeron or a high-end Core i7, will not only execute JavaScript faster, but it will do so by using less power. As noted, that’s key for battery powered devices.

Do I expect it to add an hour of extra battery life to a Chromebook during typical use? No. That’s not realistic. But even an extra 15 or 20 minutes of run-time spread out over days, weeks and months is a big benefit.

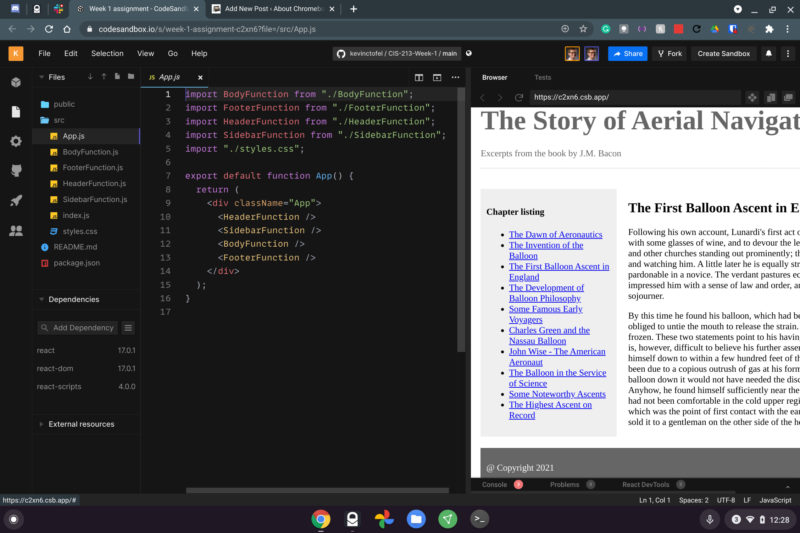

Even though I’m taking an Advanced JavaScript class this semester, we’re not touching browser rendering engines and the moving parts underneath that hood. So I’ll defer the nuts and bolts of the Sparkplug design document to someone smarter than me.

However, even with the esoteric bits abstracted away in the open-source JavaScript V8 engine, I like what I’m seeing here and can’t wait to do some testing on my Chromebook once Spartkplug arrives.

We all strongly favor of any advancement that makes Chromebooks more attractive to coders and encourages the development of PWAs as an alternative with advantages over applications that execute locally. Sparkplug sounds like a very good candidate.